4 List Some of Michelangeloã¢ââ¢s Famous Works of Art

| Michelangelo | |

|---|---|

Portrait by Daniele da Volterra, c. 1545 | |

| Born | Michelangelo di Lodovico Buonarroti Simoni 6 March 1475 Caprese, Republic of Florence |

| Died | 18 Feb 1564(1564-02-18) (anile 88) Rome, Papal States |

| Known for | Sculpture, painting, compages, and poetry |

| Notable work |

|

| Motion | Loftier Renaissance |

| Signature | |

| | |

Michelangelo di Lodovico Buonarroti Simoni (Italian: [mikeˈlandʒelo di lodoˈviːko ˌbwɔnarˈrɔːti siˈmoːni]; vi March 1475 – 18 Feb 1564), known simply as Michelangelo ([1]), was an Italian sculptor, painter, architect and poet of the High Renaissance. Born in the Democracy of Florence, his piece of work had a major influence on the development of Western fine art, particularly in relation to the Renaissance notions of humanism and naturalism. He is often considered a contender for the championship of the archetypal Renaissance man, forth with his rival and elder gimmicky, Leonardo da Vinci.[2] Given the sheer volume of surviving correspondence, sketches, and reminiscences, Michelangelo is 1 of the all-time-documented artists of the 16th century and several scholars have described Michelangelo equally the most accomplished creative person of his era.[three] [4]

He sculpted 2 of his best-known works, the Pietà and David, before the historic period of thirty. Despite property a low opinion of painting, he also created two of the virtually influential frescoes in the history of Western art: the scenes from Genesis on the ceiling of the Sistine Chapel in Rome, and The Last Judgment on its altar wall. His blueprint of the Laurentian Library pioneered Mannerist architecture.[v] At the age of 74, he succeeded Antonio da Sangallo the Younger as the builder of St. Peter'southward Basilica. He transformed the programme so that the western end was finished to his pattern, as was the dome, with some modification, subsequently his death.

Michelangelo was the first Western creative person whose biography was published while he was live.[two] In fact, two biographies were published during his lifetime. Ane of them, past Giorgio Vasari, proposed that Michelangelo's piece of work transcended that of any artist living or dead, and was "supreme in not one art lonely only in all 3."[6]

In his lifetime, Michelangelo was often chosen Il Divino ("the divine one").[7] His contemporaries oftentimes admired his terribilità—his ability to instill a sense of awe in viewers of his art. Attempts by subsequent artists to imitate[eight] Michelangelo's impassioned, highly personal way contributed to the rise of Mannerism, a short-lived fashion and period in Western art following the High Renaissance.

Life

Early life, 1475–1488

Michelangelo was built-in on half dozen March 1475[a] in Caprese, known today equally Caprese Michelangelo, a modest town situated in Valtiberina,[ix] near Arezzo, Tuscany.[x] For several generations, his family had been pocket-size bankers in Florence; merely the bank failed, and his father, Ludovico di Leonardo Buonarroti Simoni, briefly took a regime post in Caprese, where Michelangelo was born.[two] At the fourth dimension of Michelangelo'south birth, his father was the town's judicial administrator and podestà or local administrator of Chiusi della Verna. Michelangelo'southward mother was Francesca di Neri del Miniato di Siena.[11] The Buonarrotis claimed to descend from the Countess Mathilde of Canossa—a claim that remains unproven, but which Michelangelo believed.[12]

Several months later on Michelangelo's birth, the family returned to Florence, where he was raised. During his mother's later prolonged illness, and later her death in 1481 (when he was half-dozen years former), Michelangelo lived with a nanny and her husband, a stonecutter, in the boondocks of Settignano, where his father owned a marble quarry and a small farm.[eleven] There he gained his dearest for marble. As Giorgio Vasari quotes him:

If in that location is some good in me, it is because I was born in the subtle temper of your country of Arezzo. Along with the milk of my nurse I received the knack of handling chisel and hammer, with which I brand my figures.[10]

Apprenticeships, 1488–1492

As a immature boy, Michelangelo was sent to Florence to study grammer under the Humanist Francesco da Urbino.[10] [xiii] [b] However, he showed no involvement in his schooling, preferring to re-create paintings from churches and seek the company of other painters.[13]

The city of Florence was at that time Italy's greatest center of the arts and learning.[xiv] Fine art was sponsored by the Signoria (the boondocks quango), the merchant guilds, and wealthy patrons such as the Medici and their banking associates.[fifteen] The Renaissance, a renewal of Classical scholarship and the arts, had its beginning flowering in Florence.[14] In the early 15th century, the architect Filippo Brunelleschi, having studied the remains of Classical buildings in Rome, had created two churches, San Lorenzo's and Santo Spirito, which embodied the Classical precepts.[xvi] The sculptor Lorenzo Ghiberti had laboured for fifty years to create the bronze doors of the Baptistry, which Michelangelo was to draw as "The Gates of Paradise".[17] The outside niches of the Church of Orsanmichele contained a gallery of works by the most acclaimed sculptors of Florence: Donatello, Ghiberti, Andrea del Verrocchio, and Nanni di Banco.[fifteen] The interiors of the older churches were covered with frescos (more often than not in Late Medieval, but besides in the Early Renaissance style), begun past Giotto and continued by Masaccio in the Brancacci Chapel, both of whose works Michelangelo studied and copied in drawings.[18]

During Michelangelo's childhood, a team of painters had been called from Florence to the Vatican to decorate the walls of the Sistine Chapel. Amidst them was Domenico Ghirlandaio, a master in fresco painting, perspective, figure drawing and portraiture who had the largest workshop in Florence.[15] In 1488, at historic period 13, Michelangelo was apprenticed to Ghirlandaio.[19] The next year, his father persuaded Ghirlandaio to pay Michelangelo as an artist, which was rare for someone of xiv.[20] When in 1489, Lorenzo de' Medici, de facto ruler of Florence, asked Ghirlandaio for his two best pupils, Ghirlandaio sent Michelangelo and Francesco Granacci.[21]

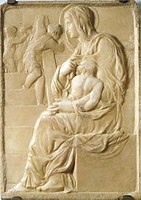

From 1490 to 1492, Michelangelo attended the Platonic Academy, a Humanist academy founded by the Medici. There, his work and outlook were influenced by many of the virtually prominent philosophers and writers of the day, including Marsilio Ficino, Pico della Mirandola and Poliziano.[22] At this time, Michelangelo sculpted the reliefs Madonna of the Steps (1490–1492) and Battle of the Centaurs (1491–1492),[18] the latter based on a theme suggested past Poliziano and deputed past Lorenzo de' Medici.[23] Michelangelo worked for a fourth dimension with the sculptor Bertoldo di Giovanni. When he was seventeen, another pupil, Pietro Torrigiano, struck him on the nose, causing the disfigurement that is conspicuous in the portraits of Michelangelo.[24]

Bologna, Florence and Rome, 1492–1499

Pietà, St Peter'south Basilica (1498–99)

Lorenzo de' Medici's expiry on eight April 1492 brought a reversal of Michelangelo'due south circumstances.[25] Michelangelo left the security of the Medici court and returned to his father's business firm. In the post-obit months he carved a polychrome wooden Crucifix (1493), as a gift to the prior of the Florentine church building of Santo Spirito, which had allowed him to do some anatomical studies of the corpses from the church'south infirmary.[26] This was the beginning of several instances during his career that Michelangelo studied beefcake by dissecting cadavers.[27] [28]

Between 1493 and 1494 he bought a block of marble, and carved a larger-than-life statue of Hercules, which was sent to France and subsequently disappeared former in the 18th century.[23] [c] On 20 Jan 1494, afterward heavy snowfalls, Lorenzo's heir, Piero de Medici, commissioned a snow statue, and Michelangelo over again entered the court of the Medici.[29]

In the same twelvemonth, the Medici were expelled from Florence as the event of the ascent of Savonarola. Michelangelo left the city before the end of the political upheaval, moving to Venice and so to Bologna.[25] In Bologna, he was commissioned to cleave several of the last small figures for the completion of the Shrine of St. Dominic, in the church dedicated to that saint. At this time Michelangelo studied the robust reliefs carved by Jacopo della Quercia around the chief portal of the Basilica of St Petronius, including the console of The Creation of Eve, the composition of which was to reappear on the Sistine Chapel ceiling.[30] Towards the end of 1495, the political situation in Florence was calmer; the city, previously under threat from the French, was no longer in danger every bit Charles Viii had suffered defeats. Michelangelo returned to Florence only received no commissions from the new metropolis government nether Savonarola.[31] He returned to the employment of the Medici.[32] During the one-half-twelvemonth he spent in Florence, he worked on two small statues, a child St. John the Baptist and a sleeping Cupid. According to Condivi, Lorenzo di Pierfrancesco de' Medici, for whom Michelangelo had sculpted St. John the Baptist, asked that Michelangelo "gear up it so that it looked equally if it had been buried" so he could "send it to Rome ... pass [it off every bit] an ancient work and ... sell information technology much improve." Both Lorenzo and Michelangelo were unwittingly cheated out of the real value of the slice by a middleman. Cardinal Raffaele Riario, to whom Lorenzo had sold information technology, discovered that it was a fraud, but was so impressed by the quality of the sculpture that he invited the artist to Rome.[33] [d] This credible success in selling his sculpture away also equally the bourgeois Florentine situation may take encouraged Michelangelo to accept the prelate's invitation.[32] Michelangelo arrived in Rome on 25 June 1496[34] at the age of 21. On 4 July of the same yr, he began work on a commission for Cardinal Riario, an over-life-size statue of the Roman wine god Bacchus. Upon completion, the work was rejected by the fundamental, and subsequently entered the collection of the banker Jacopo Galli, for his garden.

In November 1497, the French ambassador to the Holy Run across, Cardinal Jean de Bilhères-Lagraulas, deputed him to cleave a Pietà, a sculpture showing the Virgin Mary grieving over the body of Jesus. The subject, which is non part of the Biblical narrative of the Crucifixion, was mutual in religious sculpture of Medieval Northern Europe and would have been very familiar to the Cardinal.[35] The contract was agreed upon in August of the post-obit yr. Michelangelo was 24 at the time of its completion.[35] Information technology was soon to be regarded as i of the earth's groovy masterpieces of sculpture, "a revelation of all the potentialities and forcefulness of the fine art of sculpture". Contemporary opinion was summarised by Vasari: "It is certainly a miracle that a formless block of stone could always have been reduced to a perfection that nature is scarcely able to create in the mankind."[36] It is now located in St Peter's Basilica.

Florence, 1499–1505

The Statue of David, completed by Michelangelo in 1504, is one of the almost renowned works of the Renaissance.

Michelangelo returned to Florence in 1499. The Republic was changing later on the fall of its leader, anti-Renaissance priest Girolamo Savonarola, who was executed in 1498, and the rise of the gonfaloniere Piero Soderini. Michelangelo was asked by the consuls of the Society of Wool to complete an unfinished project begun 40 years before by Agostino di Duccio: a colossal statue of Carrara marble portraying David as a symbol of Florentine freedom to exist placed on the gable of Florence Cathedral.[37] Michelangelo responded by completing his virtually famous work, the statue of David, in 1504. The masterwork definitively established his prominence equally a sculptor of extraordinary technical skill and force of symbolic imagination. A team of consultants, including Botticelli, Leonardo da Vinci, Filippino Lippi, Pietro Perugino, Lorenzo di Credi, Antonio and Giuliano da Sangallo, Andrea della Robbia, Cosimo Rosselli, Davide Ghirlandaio, Piero di Cosimo, Andrea Sansovino and Michelangelo's dear friend Francesco Granacci, was called together to make up one's mind upon its placement, ultimately the Piazza della Signoria, in front end of the Palazzo Vecchio. It at present stands in the Academia while a replica occupies its place in the square.[38] In the same period of placing the David, Michelangelo may take been involved in creating the sculptural contour on Palazzo Vecchio's façade known as the Importuno di Michelangelo. The hypothesis[39] on Michelangelo'southward possible involvement in the creation of the contour is based on the stiff resemblance of the latter to a profile drawn past the creative person, datable to the outset of the 16th century, at present preserved in the Louvre.[40]

With the completion of the David came some other commission. In early 1504 Leonardo da Vinci had been commissioned to paint The Boxing of Anghiari in the quango bedroom of the Palazzo Vecchio, depicting the battle between Florence and Milan in 1440. Michelangelo was then commissioned to paint the Boxing of Cascina. The ii paintings are very different: Leonardo depicts soldiers fighting on horseback, while Michelangelo has soldiers being ambushed equally they bathe in the river. Neither work was completed and both were lost forever when the bedroom was refurbished. Both works were much admired, and copies remain of them, Leonardo's work having been copied past Rubens and Michelangelo's by Bastiano da Sangallo.[41]

Also during this period, Michelangelo was commissioned past Angelo Doni to pigment a "Holy Family" equally a present for his wife, Maddalena Strozzi. It is known as the Doni Tondo and hangs in the Uffizi Gallery in its original magnificent frame, which Michelangelo may accept designed.[42] [43] He also may take painted the Madonna and Child with John the Baptist, known every bit the Manchester Madonna and now in the National Gallery, London.[44]

Tomb of Julius II, 1505–1545

In 1505 Michelangelo was invited dorsum to Rome by the newly elected Pope Julius Two and deputed to build the Pope'south tomb, which was to include twoscore statues and be finished in five years.[45] Under the patronage of the pope, Michelangelo experienced constant interruptions to his work on the tomb in social club to accomplish numerous other tasks.

The commission for the tomb forced the artist to leave Florence with his planned Battle of Cascina painting unfinished.[46] [47] [48] By this time, Michelangelo was established as an creative person;[49] both he and Julius II had hot tempers and before long argued.[47] [48] On 17 April 1506, Michelangelo left Rome in secret for Florence, remaining in that location until the Florentine authorities pressed him to render to the pope.[48]

Although Michelangelo worked on the tomb for twoscore years, it was never finished to his satisfaction.[45] It is located in the Church of San Pietro in Vincoli in Rome and is well-nigh famous for the central figure of Moses, completed in 1516.[50] Of the other statues intended for the tomb, ii, known every bit the Rebellious Slave and the Dying Slave, are now in the Louvre.[45]

Sistine Chapel ceiling, 1505–1512

Michelangelo painted the ceiling of the Sistine Chapel; the work took approximately four years to complete (1508–1512)

During the same menstruation, Michelangelo painted the ceiling of the Sistine Chapel,[51] which took approximately four years to consummate (1508–1512).[50] According to Condivi'due south business relationship, Bramante, who was working on the building of St. Peter'southward Basilica, resented Michelangelo'southward commission for the pope'southward tomb and convinced the pope to commission him in a medium with which he was unfamiliar, in lodge that he might fail at the chore.[52] Michelangelo was originally commissioned to paint the Twelve Apostles on the triangular pendentives that supported the ceiling, and to comprehend the fundamental part of the ceiling with ornament.[53] Michelangelo persuaded Pope Julius II to give him a free manus and proposed a unlike and more complex scheme,[47] [48] representing the Cosmos, the Fall of Man, the Hope of Salvation through the prophets, and the genealogy of Christ. The work is function of a larger scheme of decoration within the chapel that represents much of the doctrine of the Catholic Church.[53]

The composition stretches over 500 foursquare metres of ceiling[54] and contains over 300 figures.[53] At its heart are nine episodes from the Volume of Genesis, divided into three groups: God's creation of the earth; God's creation of humankind and their fall from God's grace; and lastly, the state of humanity as represented by Noah and his family. On the pendentives supporting the ceiling are painted twelve men and women who prophesied the coming of Jesus, seven prophets of State of israel, and v Sibyls, prophetic women of the Classical world.[53] Among the nigh famous paintings on the ceiling are The Creation of Adam, Adam and Eve in the Garden of Eden, the Deluge, the Prophet Jeremiah, and the Cumaean Sibyl.

Florence nether Medici popes, 1513 – early on 1534

In 1513, Pope Julius 2 died and was succeeded past Pope Leo X, the second son of Lorenzo de' Medici.[50] From 1513 to 1516 Pope Leo was on skillful terms with Pope Julius'south surviving relatives, and so encouraged Michelangelo to go on work on Julius's tomb, but the families became enemies once more in 1516 when Pope Leo tried to seize the Duchy of Urbino from Julius's nephew Francesco Maria I della Rovere.[55] Pope Leo and so had Michelangelo finish working on the tomb, and commissioned him to reconstruct the façade of the Basilica of San Lorenzo in Florence and to adorn information technology with sculptures. He spent three years creating drawings and models for the façade, besides equally attempting to open a new marble quarry at Pietrasanta specifically for the project. In 1520, the work was abruptly cancelled by his financially strapped patrons before whatever real progress had been made. The basilica lacks a façade to this day.[56]

In 1520, the Medici came back to Michelangelo with another grand proposal, this time for a family funerary chapel in the Basilica of San Lorenzo.[fifty] For posterity, this project, occupying the artist for much of the 1520s and 1530s, was more fully realised. Michelangelo used his own discretion to create the composition of the Medici Chapel, which houses the large tombs of two of the younger members of the Medici family unit, Giuliano, Duke of Nemours, and Lorenzo, his nephew. It also serves to commemorate their more famous predecessors, Lorenzo the Magnificent and his brother Giuliano, who are buried nearby. The tombs brandish statues of the two Medici and emblematic figures representing Nighttime and Twenty-four hour period, and Sunset and Dawn. The chapel also contains Michelangelo's Medici Madonna.[57] In 1976 a curtained corridor was discovered with drawings on the walls that related to the chapel itself.[58] [59]

Pope Leo 10 died in 1521 and was succeeded briefly by the austere Adrian Vi, and then past his cousin Giulio Medici as Pope Clement VII.[60] In 1524 Michelangelo received an architectural commission from the Medici pope for the Laurentian Library at San Lorenzo's Church.[fifty] He designed both the interior of the library itself and its vestibule, a edifice utilising architectural forms with such dynamic result that it is seen every bit the forerunner of Baroque architecture. It was left to assistants to interpret his plans and comport out structure. The library was not opened until 1571, and the vestibule remained incomplete until 1904.[61]

In 1527, Florentine citizens, encouraged by the sack of Rome, threw out the Medici and restored the democracy. A siege of the city ensued, and Michelangelo went to the help of his honey Florence by working on the city's fortifications from 1528 to 1529. The city savage in 1530, and the Medici were restored to power.[50] Michelangelo brutal out of favour with the young Alessandro Medici, who had been installed as the first Knuckles of Florence. Fearing for his life, he fled to Rome, leaving assistants to complete the Medici chapel and the Laurentian Library. Despite Michelangelo'southward support of the commonwealth and resistance to the Medici rule, he was welcomed by Pope Clement, who reinstated an allowance that he had previously granted the artist and fabricated a new contract with him over the tomb of Pope Julius.[62]

Rome, 1534–1546

In Rome, Michelangelo lived near the church of Santa Maria di Loreto. Information technology was at this time that he met the poet Vittoria Colonna, marchioness of Pescara, who was to get one of his closest friends until her death in 1547.[63]

Presently before his death in 1534, Pope Cloudless VII commissioned Michelangelo to paint a fresco of The Last Judgment on the altar wall of the Sistine Chapel. His successor, Pope Paul Three, was instrumental in seeing that Michelangelo began and completed the projection, which he laboured on from 1534 to October 1541.[l] The fresco depicts the Second Coming of Christ and his Judgement of the souls. Michelangelo ignored the usual artistic conventions in portraying Jesus, showing him as a massive, muscular effigy, youthful, beardless and naked.[64] He is surrounded by saints, among whom Saint Bartholomew holds a drooping flayed pare, bearing the likeness of Michelangelo. The dead rise from their graves, to be consigned either to Heaven or to Hell.[64]

One time completed, the depiction of Christ and the Virgin Mary naked was considered sacrilegious, and Primal Carafa and Monsignor Sernini (Mantua'southward ambassador) campaigned to have the fresco removed or censored, merely the Pope resisted. At the Council of Trent, soon before Michelangelo's death in 1564, it was decided to obscure the genitals and Daniele da Volterra, an amateur of Michelangelo, was deputed to brand the alterations.[65] An uncensored re-create of the original, by Marcello Venusti, is in the Capodimonte Museum of Naples.[66]

Michelangelo worked on a number of architectural projects at this time. They included a design for the Capitoline Hill with its trapezoid piazza displaying the aboriginal statuary statue of Marcus Aurelius. He designed the upper floor of the Palazzo Farnese and the interior of the Church building of Santa Maria degli Angeli, in which he transformed the vaulted interior of an Aboriginal Roman bathhouse. Other architectural works include San Giovanni dei Fiorentini, the Sforza Chapel (Capella Sforza) in the Basilica di Santa Maria Maggiore and the Porta Pia.[67]

St Peter's Basilica, 1546–1564

While nevertheless working on the Terminal Judgment, Michelangelo received yet another committee for the Vatican. This was for the painting of two large frescos in the Cappella Paolina depicting pregnant events in the lives of the two nigh important saints of Rome, the Conversion of Saint Paul and the Crucifixion of Saint Peter. Similar the Last Judgment, these two works are complex compositions containing a nifty number of figures.[68] They were completed in 1550. In the same year, Giorgio Vasari published his Vita, including a biography of Michelangelo.[69]

In 1546, Michelangelo was appointed builder of St. Peter's Basilica, Rome.[fifty] The process of replacing the Constantinian basilica of the 4th century had been underway for 50 years and in 1506 foundations had been laid to the plans of Bramante. Successive architects had worked on it, but little progress had been made. Michelangelo was persuaded to take over the project. He returned to the concepts of Bramante, and developed his ideas for a centrally planned church, strengthening the structure both physically and visually.[70] The dome, not completed until after his death, has been called by Banister Fletcher, "the greatest cosmos of the Renaissance".[71]

As construction was progressing on St Peter's, there was concern that Michelangelo would laissez passer away earlier the dome was finished. However, one time edifice commenced on the lower part of the dome, the supporting ring, the completion of the design was inevitable.

On 7 December 2007, a red chalk sketch for the dome of St Peter's Basilica, possibly the last made past Michelangelo before his death, was discovered in the Vatican archives. Information technology is extremely rare, since he destroyed his designs later in life. The sketch is a fractional plan for one of the radial columns of the cupola drum of Saint Peter's.[72]

Personal life

Faith

Michelangelo was a devout Cosmic whose religion deepened at the end of his life.[73] His verse includes the following closing lines from what is known as verse form 285 (written in 1554); "Neither painting nor sculpture will be able any longer to calm my soul, now turned toward that divine love that opened his arms on the cross to take united states in." [74] [75]

Personal habits

Michelangelo was abstemious in his personal life, and once told his apprentice, Ascanio Condivi: "Even so rich I may have been, I have always lived like a poor homo."[76] Michelangelo'south bank accounts and numerous deeds of purchase show that his cyberspace worth was nearly 50,000 gold ducats, more than many princes and dukes of his time.[77] Condivi said he was indifferent to food and beverage, eating "more than out of necessity than of pleasure"[76] and that he "often slept in his clothes and ... boots."[76] His biographer Paolo Giovio says, "His nature was so rough and uncouth that his domestic habits were incredibly squalid, and deprived posterity of any pupils who might have followed him."[78] This, nonetheless, may not take affected him, every bit he was by nature a solitary and melancholy person, bizzarro due east fantastico , a human being who "withdrew himself from the visitor of men."[79]

Relationships and poesy

It is impossible to know for certain whether Michelangelo had physical relationships (Condivi ascribed to him a "monk-like guiltlessness");[80] speculation about his sexuality is rooted in his poetry.[81] He wrote over 3 hundred sonnets and madrigals. The longest sequence, displaying deep romantic feeling, was written to the immature Roman patrician Tommaso dei Cavalieri (c. 1509–1587), who was 23 years old when Michelangelo start met him in 1532, at the age of 57.[82] [83] The Florentine Benedetto Varchi fifteen years afterwards described Cavalieri as of "unequalled beauty", with "graceful manners, so excellent an endowment and so charming a demeanour that he indeed deserved, and still deserves, the more to be loved the better he is known".[84] In his "Lives of the Artists", Giorgio Vasari observed: "Simply infinitely more than any of the others he loved M. Tommaso de' Cavalieri, a Roman admirer, for whom, being a young man and much inclined to these arts, [Michelangelo] made, to the terminate that he might learn to describe, many most superb drawings of divinely beautiful heads, designed in black and red chalk; and so he drew for him a Ganymede rapt to Heaven past Jove's Eagle, a Tityus with the Vulture devouring his heart, the Chariot of the Sun falling with Phaëthon into the Po, and a Bacchanalia of children, which are all in themselves most rare things, and drawings the like of which accept never been seen."[85] Scholars agree that Michelangelo became infatuated with Cavalieri.[86] The poems to Cavalieri brand up the outset large sequence of poems in any modern tongue addressed past one man to another; they predate by 50 years Shakespeare's sonnets to the fair youth:

I feel as lit by fire a cold countenance

That burns me from distant and keeps itself ice-chill;

A forcefulness I feel two shapely arms to make full

Which without movement moves every balance.

-

- — (Michael Sullivan, translation)

Cavalieri replied: "I swear to return your love. Never have I loved a man more than I beloved you, never take I wished for a friendship more I wish for yours." Cavalieri remained devoted to Michelangelo until his expiry.[87]

In 1542, Michelangelo met Cecchino dei Bracci who died merely a yr afterwards, inspiring Michelangelo to write 48 funeral epigrams. Some of the objects of Michelangelo'south affections, and subjects of his poesy, took advantage of him: the model Febo di Poggio asked for money in response to a love-poem, and a 2d model, Gherardo Perini, stole from him shamelessly.[87]

What some have interpreted as the seemingly homoerotic nature of the poetry has been a source of discomfort to later generations. Michelangelo's grandnephew, Michelangelo Buonarroti the Younger, published the poems in 1623 with the gender of pronouns changed,[88] and it was not until John Addington Symonds translated them into English in 1893 that the original genders were restored. In modern times some scholars insist that, despite the restoration of the pronouns, they stand for "an emotionless and elegant re-imagining of Ideal dialogue, whereby erotic poetry was seen as an expression of refined sensibilities".[87]

Late in life, Michelangelo nurtured a great platonic love for the poet and noble widow Vittoria Colonna, whom he met in Rome in 1536 or 1538 and who was in her belatedly forties at the time. They wrote sonnets for each other and were in regular contact until she died. These sonnets more often than not deal with the spiritual problems that occupied them.[89] Condivi recalls Michelangelo's saying that his sole regret in life was that he did not buss the widow's confront in the same manner that he had her paw.[63]

Feuds with other artists

In a letter of the alphabet from late 1542, Michelangelo blamed the tensions betwixt Julius Two and himself on the envy of Bramante and Raphael, saying of the latter, "all he had in art, he got from me". Co-ordinate to Gian Paolo Lomazzo, Michelangelo and Raphael met once: the onetime was alone, while the latter was accompanied by several others. Michelangelo commented that he thought he had encountered the main of police with such an assemblage, and Raphael replied that he idea he had met an executioner, as they are wont to walk solitary.[90]

Works

Madonna and Child

The Madonna of the Steps is Michelangelo's earliest known work in marble. It is carved in shallow relief, a technique frequently employed by the master-sculptor of the early 15th century, Donatello, and others such as Desiderio da Settignano.[91] While the Madonna is in profile, the easiest aspect for a shallow relief, the child displays a twisting motion that was to become feature of Michelangelo'southward work. The Taddei Tondo of 1502 shows the Christ Child frightened past a Bullfinch, a symbol of the Crucifixion.[42] The lively form of the child was later adapted by Raphael in the Bridgewater Madonna. The Bruges Madonna was, at the time of its creation, different other such statues depicting the Virgin proudly presenting her son. Here, the Christ Child, restrained past his mother'due south clasping hand, is nearly to step off into the earth.[92] The Doni Tondo, depicting the Holy Family, has elements of all three previous works: the frieze of figures in the groundwork has the appearance of a low-relief, while the round shape and dynamic forms echo the Taddeo Tondo. The twisting motility present in the Bruges Madonna is accentuated in the painting. The painting heralds the forms, movement and color that Michelangelo was to utilise on the ceiling of the Sistine Chapel.[42]

-

-

The Taddei Tondo (1502)

Male person figure

The kneeling angel is an early on work, one of several that Michelangelo created equally part of a big decorative scheme for the Arca di San Domenico in the church defended to that saint in Bologna. Several other artists had worked on the scheme, beginning with Nicola Pisano in the 13th century. In the late 15th century, the project was managed by Niccolò dell'Arca. An angel holding a candlestick, by Niccolò, was already in place.[93] Although the two angels class a pair, there is a peachy dissimilarity between the 2 works, the one depicting a frail child with flowing hair clothed in Gothic robes with deep folds, and Michelangelo'southward depicting a robust and muscular youth with eagle'south wings, clad in a garment of Classical style. Everything near Michelangelo's angel is dynamic.[94] Michelangelo's Bacchus was a commission with a specified subject, the youthful God of Wine. The sculpture has all the traditional attributes, a vine wreath, a cup of wine and a fawn, simply Michelangelo ingested an air of reality into the field of study, depicting him with bleary optics, a bloated bladder and a stance that suggests he is unsteady on his feet.[93] While the work is plainly inspired by Classical sculpture, it is innovative for its rotating movement and strongly three-dimensional quality, which encourages the viewer to look at it from every angle.[95]

In the so-called Dying Slave, Michelangelo over again utilised the effigy with marked contrapposto to suggest a particular human state, in this case waking from sleep. With the Rebellious Slave, it is 1 of two such earlier figures for the Tomb of Pope Julius 2, now in the Louvre, that the sculptor brought to an almost finished country.[96] These two works were to have a profound influence on after sculpture, through Rodin who studied them at the Louvre.[97] The Atlas Slave is one of the later figures for Pope Julius' tomb. The works, known collectively every bit The Captives, each show the figure struggling to free itself, as if from the bonds of the stone in which it is lodged. The works give a unique insight into the sculptural methods that Michelangelo employed and his manner of revealing what he perceived within the rock.[98]

-

Angel by Michelangelo, early piece of work (1494–95)

-

Bacchus by Michelangelo, early work (1496–1497)

-

-

Sistine Chapel ceiling

The Sistine Chapel ceiling was painted between 1508 and 1512.[50] The ceiling is a flattened barrel vault supported on twelve triangular pendentives that rise from between the windows of the chapel. The commission, as envisaged by Pope Julius Two, was to beautify the pendentives with figures of the twelve apostles.[99] Michelangelo, who was reluctant to take the job, persuaded the Pope to give him a free paw in the composition.[100] The resultant scheme of ornamentation awed his contemporaries and has inspired other artists ever since.[101] The scheme is of ix panels illustrating episodes from the Book of Genesis, set in an architectonic frame. On the pendentives, Michelangelo replaced the proposed Apostles with Prophets and Sibyls who heralded the coming of the Messiah.[100]

The Sistine Chapel Ceiling (1508–1512)

Michelangelo began painting with the after episodes in the narrative, the pictures including locational details and groups of figures, the Drunkenness of Noah being the commencement of this group.[100] In the later compositions, painted after the initial scaffolding had been removed, Michelangelo made the figures larger.[100] One of the key images, The Creation of Adam is one of the best known and most reproduced works in the history of fine art. The last panel, showing the Separation of Light from Darkness is the broadest in fashion and was painted in a single day. As the model for the Creator, Michelangelo has depicted himself in the action of painting the ceiling.[100]

-

The Drunkenness of Noah

-

The Deluge (item)

-

-

The Kickoff Day of Creation

As supporters to the smaller scenes, Michelangelo painted twenty youths who have variously been interpreted as angels, as muses, or only as decoration. Michelangelo referred to them every bit "ignudi".[102] The figure reproduced may be seen in context in the above image of the Separation of Light from Darkness. In the process of painting the ceiling, Michelangelo made studies for different figures, of which some, such every bit that for The Libyan Sibyl have survived, demonstrating the care taken by Michelangelo in details such as the easily and feet.[103] The Prophet Jeremiah, contemplating the downfall of Jerusalem, is an image of the artist himself.

-

Studies for The Libyan Sibyl

-

The Libyan Sibyl (1511)

-

The Prophet Jeremiah (1511)

-

Ignudo

Figure compositions

Michelangelo's relief of the Boxing of the Centaurs, created while he was still a youth associated with the Medici Academy,[104] is an unusually circuitous relief in that it shows a great number of figures involved in a vigorous struggle. Such a complex disarray of figures was rare in Florentine art, where information technology would usually only exist found in images showing either the Massacre of the Innocents or the Torments of Hell. The relief treatment, in which some of the figures are boldly projecting, may point Michelangelo's familiarity with Roman sarcophagus reliefs from the collection of Lorenzo Medici, and similar marble panels created by Nicola and Giovanni Pisano, and with the figurative compositions on Ghiberti'southward Baptistry Doors.[ citation needed ]

The composition of the Battle of Cascina is known in its entirety just from copies,[105] as the original cartoon, according to Vasari, was so admired that information technology deteriorated and was somewhen in pieces.[106] It reflects the earlier relief in the free energy and variety of the figures,[107] with many different postures, and many being viewed from the dorsum, as they turn towards the approaching enemy and prepare for battle.[ citation needed ]

In The Terminal Judgment it is said that Michelangelo drew inspiration from a fresco past Melozzo da Forlì in Rome'south Santi Apostoli. Melozzo had depicted figures from different angles, every bit if they were floating in the Heaven and seen from below. Melozzo's majestic figure of Christ, with windblown cloak, demonstrates a degree of foreshortening of the figure that had also been employed by Andrea Mantegna, just was not usual in the frescos of Florentine painters. In The Last Judgment Michelangelo had the opportunity to depict, on an unprecedented scale, figures in the activity of either rise heavenward or falling and beingness dragged down.[ citation needed ]

In the two frescos of the Pauline Chapel, The Crucifixion of St. Peter and The Conversion of Saul, Michelangelo has used the various groups of figures to convey a complex narrative. In the Crucifixion of Peter soldiers busy themselves virtually their assigned duty of digging a mail service pigsty and raising the cross while various people await on and discuss the events. A group of horrified women cluster in the foreground, while another group of Christians is led by a tall human being to witness the events. In the right foreground, Michelangelo walks out of the painting with an expression of disillusionment.[ citation needed ]

Architecture

Michelangelo's architectural commissions included a number that were not realised, notably the façade for Brunelleschi's Church of San Lorenzo in Florence, for which Michelangelo had a wooden model synthetic, but which remains to this solar day unfinished rough brick. At the aforementioned church, Giulio de' Medici (later Pope Clement VII) commissioned him to design the Medici Chapel and the tombs of Giuliano and Lorenzo Medici.[108] Pope Clement also commissioned the Laurentian Library, for which Michelangelo besides designed the extraordinary anteroom with columns recessed into niches, and a staircase that appears to spill out of the library like a flow of lava, according to Nikolaus Pevsner, "... revealing Mannerism in its most sublime architectural course."[109]

In 1546 Michelangelo produced the highly circuitous ovoid design for the pavement of the Campidoglio and began designing an upper storey for the Farnese Palace. In 1547 he took on the job of completing St Peter's Basilica, begun to a design by Bramante, and with several intermediate designs by several architects. Michelangelo returned to Bramante's design, retaining the basic course and concepts by simplifying and strengthening the design to create a more dynamic and unified whole.[110] Although the belatedly 16th-century engraving depicts the dome as having a hemispherical profile, the dome of Michelangelo's model is somewhat ovoid and the final product, every bit completed by Giacomo della Porta, is more than and then.[110]

-

Michelangelo'south redesign of the ancient Capitoline Hill included a circuitous spiralling pavement with a star at its centre.

-

Michelangelo's design for St Peter'southward is both massive and contained, with the corners between the apsidal arms of the Greek Cantankerous filled by square projections.

-

The outside is surrounded by a giant order of pilasters supporting a continuous cornice. Four small cupolas cluster effectually the dome.

Concluding years

In his erstwhile historic period, Michelangelo created a number of Pietàs in which he apparently reflects upon mortality. They are heralded by the Victory, perhaps created for the tomb of Pope Julius II but left unfinished. In this group, the youthful victor overcomes an older hooded figure, with the features of Michelangelo.

The Pietà of Vittoria Colonna is a chalk drawing of a type described as "presentation drawings", as they might be given as a souvenir by an artist, and were not necessarily studies towards a painted work. In this image, Mary's upraised arms and hands are indicative of her prophetic role. The frontal aspect is reminiscent of Masaccio'due south fresco of the Holy Trinity in the Basilica of Santa Maria Novella, Florence.

In the Florentine Pietà, Michelangelo again depicts himself, this time as the aged Nicodemus lowering the trunk of Jesus from the cross into the arms of Mary his mother and Mary Magdalene. Michelangelo smashed the left arm and leg of the figure of Jesus. His pupil Tiberio Calcagni repaired the arm and drilled a pigsty in which to set up a replacement leg which was not subsequently attached. He too worked on the figure of Mary Magdalene.[111] [112]

The last sculpture that Michelangelo worked on (six days before his death), the Rondanini Pietà could never be completed because Michelangelo carved information technology away until in that location was bereft stone. The legs and a detached arm remain from a previous stage of the work. Every bit it remains, the sculpture has an abstract quality, in keeping with 20th-century concepts of sculpture.[113] [114]

Michelangelo died in Rome in 1564, at the age of 88 (3 weeks before his 89th birthday). His torso was taken from Rome for interment at the Basilica of Santa Croce, fulfilling the maestro's last asking to exist buried in his beloved Florence.[115]

Michelangelo's heir Lionardo Buonarroti commissioned Giorgio Vasari to design and build the Tomb of Michelangelo, a monumental project that cost 770 scudi, and took over 14 years to complete.[116] Marble for the tomb was supplied past Cosimo I de' Medici, Duke of Tuscany who had also organized a state funeral to honor Michelangelo in Florence.[116]

-

Statue of Victory (1534), Palazzo Vecchio, Florence

-

The Pietà of Vittoria Colonna (c. 1540)

In popular culture

- Movies

- Vita di Michelangelo (1964)[117]

- The Agony and the Ecstasy (1965), directed past Ballad Reed and starring Charlton Heston as Michelangelo[118]

- A Flavor of Giants (1990)[119] [120] [121]

- Michelangelo - Endless (2018), starring Enrico Lo Verso as Michelangelo[122]

- Sin (2019), directed past Andrei Konchalovsky[123]

Legacy

Michelangelo, with Leonardo da Vinci and Raphael, is one of the 3 giants of the Florentine High Renaissance. Although their names are often cited together, Michelangelo was younger than Leonardo past 23 years, and older than Raphael past eight. Because of his reclusive nature, he had little to do with either creative person and outlived both of them by more than than forty years. Michelangelo took few sculpture students. He employed Francesco Granacci, who was his young man pupil at the Medici Academy, and became ane of several assistants on the Sistine Chapel ceiling.[53] Michelangelo appears to have used administration mainly for the more than manual tasks of preparing surfaces and grinding colours. Despite this, his works were to accept a great influence on painters, sculptors and architects for many generations to come.

While Michelangelo'south David is the most famous male person nude of all fourth dimension and now graces cities around the world, some of his other works have had peradventure even greater affect on the course of art. The twisting forms and tensions of the Victory, the Bruges Madonna and the Medici Madonna make them the heralds of the Mannerist fine art. The unfinished giants for the tomb of Pope Julius Two had profound effect on late-19th- and 20th-century sculptors such as Rodin and Henry Moore.

Michelangelo'due south lobby of the Laurentian Library was one of the primeval buildings to utilise Classical forms in a plastic and expressive mode. This dynamic quality was later to observe its major expression in Michelangelo's centrally planned St Peter'south, with its behemothic social club, its rippling cornice and its upward-launching pointed dome. The dome of St Peter's was to influence the edifice of churches for many centuries, including Sant'Andrea della Valle in Rome and St Paul'southward Cathedral, London, as well as the borough domes of many public buildings and the state capitals across America.

Artists who were directly influenced past Michelangelo include Raphael, whose awe-inspiring treatment of the figure in the School of Athens and The Expulsion of Heliodorus from the Temple owes much to Michelangelo, and whose fresco of Isaiah in Sant'Agostino closely imitates the older master's prophets.[124] Other artists, such as Pontormo, drew on the writhing forms of the Last Judgment and the frescoes of the Capella Paolina.[125]

The Sistine Chapel ceiling was a work of unprecedented grandeur, both for its architectonic forms, to exist imitated past many Bizarre ceiling painters, and also for the wealth of its creativity in the study of figures. Vasari wrote:

The work has proved a veritable buoy to our art, of inestimable benefit to all painters, restoring light to a world that for centuries had been plunged into darkness. Indeed, painters no longer need to seek for new inventions, novel attitudes, clothed figures, fresh ways of expression, different arrangements, or sublime subjects, for this piece of work contains every perfection possible nether those headings.[106]

Encounter as well

- Michelangelo and the Medici

- Michelangelo phenomenon

- Nicodemite

- Italian Renaissance painting

- Restoration of the Sistine Chapel frescoes

- The Agony and the Ecstasy

- The Titan: Story of Michelangelo (1950 documentary)

Footnotes

- a. ^ Michelangelo's father marks the appointment as six March 1474 in the Florentine manner ab Incarnatione. Nonetheless, in the Roman manner, ab Nativitate, it is 1475.

- b. ^ Sources disagree as to how old Michelangelo was when he departed for school. De Tolnay writes that it was at 10 years old while Sedgwick notes in her translation of Condivi that Michelangelo was 7.

- c. ^ The Strozzi family unit acquired the sculpture Hercules. Filippo Strozzi sold it to Francis I in 1529. In 1594, Henry IV installed it in the Jardin d'Estang at Fontainebleau where it disappeared in 1713 when the Jardin d'Estange was destroyed.

- d. ^ Vasari makes no mention of this episode and Paolo Giovio'south Life of Michelangelo indicates that Michelangelo tried to pass the statue off as an antiquarian himself.

References

- ^ Wells, John (three April 2008). Longman Pronunciation Dictionary (3rd ed.). Pearson Longman. ISBN978-1-4058-8118-0.

- ^ a b c Michelangelo at the Encyclopædia Britannica

- ^ Symonds, John (ix Jan 2019). The Life of Michelangelo. BookRix. ISBN9783736804630 – via Google Books.

- ^ Vasari, Giorgio (14 August 2008). The Lives of the Artists. Oxford University Press. ISBN9780199537198 – via Google Books.

- ^ Hughes, A., & Elam, C. (2003). "Michelangelo". Oxford Art Online. Retrieved 14 Apr 2018, from http://www.oxfordartonline.com

- ^ Smithers, Tamara. 2016. Michelangelo in the New Millennium: Conversations about Artistic Practice, Patronage and Christianity. Boston: Brill. p. vii. ISBN 978-90-04-31362-0.

- ^ Emison, Patricia. A (2004). Creating the "Divine Artist": from Dante to Michelangelo. Brill. ISBN978-ninety-04-13709-7.

- ^ Fine art and Illusion, E.H. Gombrich, ISBN 978-0-691-07000-1

- ^ Unione Montana dei Comuni della Valtiberina Toscana, www.cm-valtiberina.toscana.it

- ^ a b c J. de Tolnay, The Youth of Michelangelo, p. xi

- ^ a b C. Clément, Michelangelo, p. 5

- ^ A. Condivi, The Life of Michelangelo, p. 5

- ^ a b A. Condivi, The Life of Michelangelo, p. ix

- ^ a b Coughlan, Robert; (1978), The World of Michelangelo, Time-Life; pp. 14–xv

- ^ a b c Coughlan, pp. 35–40

- ^ Giovanni Fanelli, (1980) Brunelleschi, Becocci Firenze, pp. 3–x

- ^ H. Gardner, p. 408

- ^ a b Coughlan, pp. 28–32

- ^ R. Liebert, Michelangelo: A Psychoanalytic Study of his Life and Images, p. 59

- ^ C. Clément, Michelangelo, p. 7

- ^ C. Clément, Michelangelo, p. 9

- ^ J. de Tolnay, The Youth of Michelangelo, pp. xviii–19

- ^ a b A. Condivi, The Life of Michelangelo, p. fifteen

- ^ Coughlan, p. 42

- ^ a b J. de Tolnay, The Youth of Michelangelo, pp. 20–21

- ^ A. Condivi, The Life of Michelangelo, p. 17

- ^ Laurenzo, Domenico (2012). Art and Anatomy in Renaissance Italy: Images from a Scientific Revolution. Metropolitan Museum of Art. p. 15. ISBN 1588394565.

- ^ Zeybek, A.; Özkan, Chiliad. (Baronial 2019). "Michelangelo and Beefcake". Anatomy: International Journal of Experimental & Clinical Anatomy. 13 (Supplement 2): S199.

- ^ Coughlan, Robert (1966). The Earth of Michelangelo: 1475–1564 . et al. Time-Life Books. p. 67.

- ^ Bartz and König, p. 54

- ^ Miles Unger, Michelangelo: a Life in Six Masterpieces, ch. one

- ^ a b J. de Tolnay, The Youth of Michelangelo, pp. 24–25

- ^ A. Condivi, The Life of Michelangelo, pp. xix–xx

- ^ J. de Tolnay, The Youth of Michelangelo, pp. 26–28

- ^ a b Hirst and Dunkerton pp. 47–55

- ^ Vasari, Lives of the painters: Michelangelo

- ^ Paoletti and Radke, pp. 387–89

- ^ Goldscheider, p. ten

- ^ Marinazzo, Adriano (2020). "Una nuova possible attribuzione a Michelangelo. Il Volto Misterioso". Art e Dossier. 379: 76–81.

- ^ "Avant Banksy et Invader, Michel-Ange pionnier du street art dans les rues de Florence". LEFIGARO (in French). 22 November 2020. Retrieved eleven April 2021.

- ^ Paoletti and Radke, pp. 392–93

- ^ a b c Goldscheider, p. 11

- ^ Hirst and Dunkerton, p. 127

- ^ Hirst and Dunkerton, pp. 83–105, 336–46

- ^ a b c Goldscheider, pp. xiv–16

- ^ Chilvers, Ian, ed. (2009). "Michelangelo (Michelangelo Buonarroti)". The Oxford Dictionary of Art and Artists (4th ed.). Online: Oxford Academy Press. doi:10.1093/acref/9780199532940.001.0001. ISBN978-0-19-953294-0.

- ^ a b c Campbell, Gordon, ed. (2005). "Michelangelo Buonarroti or Michelagnolo Buonarroti". The Oxford Dictionary of the Renaissance (Online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/acref/9780198601753.001.0001. ISBN978-0-xix-860175-3.

- ^ a b c d Osborne, Harold; Brigstocke, Hugh (2003). "Michelangelo Buonarroti". In Brigstocke, Hugh (ed.). The Oxford Companion to Western Art (Online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:x.1093/acref/9780198662037.001.0001. ISBN978-0-19-866203-7.

- ^ Pater, Walter (1893). The Renaissance: Studies in Art and Poesy (quaternary ed.). Courier Corporation [2005, 2013 reprint]. p. 55. ISBN978-0-486-14648-v.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Bartz and König, p. 134

- ^ Marinazzo, Adriano (2018). "La Tomba di Giulio II e l'architettura dipinta della volta della Sistina". Art e Dossier. 357: 46–51. ISSN 0394-0179.

- ^ Coughlan, p. 112

- ^ a b c d eastward Goldscheider, pp. 12–fourteen

- ^ Bartz and König, p. 43

- ^ Miles Unger, Michelangelo: a Life in Six Masterpieces, ch. 5

- ^ Coughlan, pp. 135–36

- ^ Goldscheider, pp. 17–18

- ^ Peter Barenboim, Sergey Shiyan, Michelangelo: Mysteries of Medici Chapel, SLOVO, Moscow, 2006. ISBN five-85050-825-two

- ^ Peter Barenboim, "Michelangelo Drawings – Key to the Medici Chapel Interpretation", Moscow, Letny Distressing, 2006, ISBN 5-98856-016-4

- ^ Coughlan, pp. 151–52

- ^ Bartz and König, p. 87

- ^ Coughlan, pp. 159–61

- ^ a b A. Condivi (ed. Hellmut Wohl), The Life of Michelangelo, p. 103, Phaidon, 1976.

- ^ a b Bartz and König, pp. 100–02

- ^ Bartz and König, pp. 102, 109

- ^ Goldscheider, pp. 19–20

- ^ Goldscheider, pp. eight, 21, 22

- ^ Bartz and Kŏnig, p. 16

- ^ Ilan Rachum, The Renaissance, an Illustrated Encyclopedia, Octopus (1979) ISBN 0-7064-0857-8

- ^ Gardner, pp. 480–81

- ^ Banister Fletcher, 17th ed. p. 719

- ^ "Michelangelo 'terminal sketch' establish". BBC News. 7 December 2007. Retrieved 9 February 2009.

- ^ "Crucifixion by Michelangelo, a cartoon in black chalk". The British Museum. Archived from the original on 15 October 2015. Retrieved 24 Oct 2018.

- ^ "Michelangelo, Selected Poems" (PDF). Columbia Academy. p. 20. Retrieved 24 October 2018.

- ^ "Michelangelo's Poetry". Michelangelo Gallery. Translated by Longfellow, H.W. Studio of the South. Retrieved 24 Oct 2018.

- ^ a b c Condivi, The Life of Michelangelo, p. 106.

- ^ Shirbon, Estelle. "Michelangelo more a prince than a pauper". LA Times.

{{cite news}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ Paola Barocchi (ed.) Scritti d'arte del cinquecento, Milan, 1971; vol. I p. x.

- ^ Condivi, p. 102.

- ^ Hughes, Anthony, "Michelangelo", p. 326. Phaidon, 1997.

- ^ Scigliano, Eric: "Michelangelo'southward Mountain; The Quest for Perfection in the Marble Quarries of Carrara" Archived 30 June 2009 at the Wayback Machine, Simon and Schuster, 2005. Retrieved 27 January 2007

- ^ Zöllner, Frank; Thoenes, Christof (2019). Michelangelo, 1475–1564: The Consummate Paintings, Sculptures and Architecture. Translated by Karen Williams (2nd ed.). Cologne: Taschen. pp. 381, 384, 387–390. ISBN978-3-8365-3716-two. OCLC 1112202167.

- ^ Bredekamp, Horst (2021). Michelangelo (in German). Verlag Klaus Wagenbach. Berlin. pp. 466–486. ISBN978-iii-8031-3707-four. OCLC 1248717101.

- ^ Gayford 2013

- ^ Vasari, Giorgio (1914). Lives of the most eminent painters, sculptors, and architects. Vol. Ix. Translated past Gaston du C. De Vere. London: Medici Society. pp. 105–106.

- ^ According to Gayford (2013), "Whatever the strength of his feelings, Michelangelo's relationship with Tommaso de'Cavalieri is unlikely to have been a physical, sexual affair. For ane thing, it was acted out through poems and images that were far from hugger-mugger. Even if we do not choose to believe Michelangelo'south protestations of the chastity of his behaviour, Tommaso'south loftier social position and the relatively public nature of their relationship get in improbable that it was not platonic."

- ^ a b c Hughes, Anthony: "Michelangelo", p. 326. Phaidon, 1997.

- ^ Rictor Norton, "The Myth of the Modernistic Homosexual", p. 143. Cassell, 1997.

- ^ Vittoria Colonna, Sonnets for Michelangelo. A Bilingual Edition edited and translated by Abigail Brundin, The University of Chicago Press 2005. ISBN 0-226-11392-2, p. 29.

- ^ Salmi, Mario; Becherucci, Luisa; Marabottini, Alessandro; Tempesti, Anna Forlani; Marchini, Giuseppe; Becatti, Giovanni; Castagnoli, Ferdinando; Golzio, Vincenzo (1969). The Complete Work of Raphael. New York: Reynal and Co., William Morrow and Visitor. pp. 587, 610.

- ^ Bartz and König, p. 8

- ^ Bartz and König, p. 22

- ^ a b Goldscheider, p. 9

- ^ Hirst and Dunkerton, pp. 20–21

- ^ Bartz and König, pp. 26–27

- ^ Bartz and König, pp. 62–63

- ^ Yvon Taillandier, Rodin, New York: Crown Trade Paperbacks, (1977) ISBN 0-517-88378-3

- ^ Coughlan, pp. 166–67

- ^ Goldscieder p. 12

- ^ a b c d due east Paoletti and Radke, pp. 402–03

- ^ Vasari, et al.

- ^ Bartz and König

- ^ Coughlan

- ^ J. de Tolnay, The Youth of Michelangelo, p. xviii

- ^ Goldscheider, p. eight

- ^ a b Giorgio Vasari, Lives of the Artists: Michelangelo

- ^ J. de Tolnay, The Youth of Michelangelo, p. 135

- ^ Goldscheider

- ^ Nikolaus Pevsner, An Outline of European Architecture, Pelican, 1964

- ^ a b Gardner

- ^ Maiorino, Giancarlo, 1990. The Cornucopian Mind and the Baroque Unity of the Arts. Penn Country Press. p. 28. ISBN 0-271-00679-X.

- ^ Di Cagno, Gabriella. 2008. Michelangelo. Oliver Press. p. 58. ISBN i-934545-01-5.

- ^ Tolnay, Charles de. 1960. Michelangelo.: V, The Final Period: Terminal Judgment. Frescoes of the Pauline Chapel. Concluding Pietas Princeton: Princeton Univ. Press. p. 154. OCLC 491820830.

- ^ Crispina, Enrica. 2001. Michelangelo. Firenze: Giunti. p. 117. ISBN 88-09-02274-2.

- ^ Coughlan, p. 179

- ^ a b "Michelangelo's tomb: five fun facts yous probably didn't know". The Florentine. 12 Oct 2017. Retrieved 20 May 2021.

- ^ "Vita di Michelangelo". imdb.com. xiii Dec 1964. Retrieved 29 Nov 2019.

- ^ Stone, Irving (1961). The Desperation and the Ecstasy: A Biographical Novel of Michelangelo . ISBN0451171357.

- ^ Ken Tucker (fifteen March 1991). "A Flavour of Giants (1991)". Entertainment Weekly . Retrieved 11 July 2014.

- ^ Hal Erickson (2014). "A Season of Giants (1991)". Movies & TV Dept. The New York Times. Archived from the original on 16 July 2014. Retrieved 11 July 2014.

- ^ VV.AA. (March 1994). Multifariousness Television Reviews, 1991–1992. Taylor & Francis, 1994. ISBN0824037960.

- ^ "Michelangelo – Endless". filmitalia.org. Retrieved 29 November 2019.

- ^ "Il Peccato, 2019" (in Russian). kinopoisk.ru. Retrieved 29 November 2019.

- ^ Ettlinger, Leopold David, and Helen South. Ettlinger. 1987. Raphael. Oxford: Phaidon. pp. 91, 102, 122. ISBN 0-7148-2303-1.

- ^ Acidini Luchinat, Cristina. 2002. The Medici, Michelangelo, and the Art of Late Renaissance Florence. New Haven: Yale University Press in association with the Detroit Institute of Arts. p. 96. ISBN 0-300-09495-7.

Sources

- Bartz, Gabriele; Eberhard König (1998). Michelangelo. Könemann. ISBN978-3-8290-0253-0.

- Clément, Charles (1892). Michelangelo . Harvard University: South. Low, Marston, Searle, & Rivington, ltd.: London.

michelangelo.

- Condivi, Ascanio; Alice Sedgewick (1553). The Life of Michelangelo. Pennsylvania Country University Press. ISBN978-0-271-01853-9.

- Goldscheider, Ludwig (1953). Michelangelo: Paintings, Sculptures, Compages. Phaidon.

- Goldscheider, Ludwig (1953). Michelangelo: Drawings. Phaidon.

- Gardner, Helen; Fred South. Kleiner, Christin J. Mamiya, Gardner's Art through the Ages. Thomson Wadsworth, (2004) ISBN 0-15-505090-7.

- Hirst, Michael and Jill Dunkerton. (1994) The Young Michelangelo: The Creative person in Rome 1496–1501. London: National Gallery Publications, ISBN ane-85709-066-7

- Liebert, Robert (1983). Michelangelo: A Psychoanalytic Study of his Life and Images. New Haven and London: Yale Academy Press. ISBN978-0-300-02793-8.

- Paoletti, John T. and Radke, Gary M., (2005) Art in Renaissance Italian republic, Laurence King, ISBN 1-85669-439-9

- Tolnay, Charles (1947). The Youth of Michelangelo . Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Further reading

- Ackerman, James (1986). The Architecture of Michelangelo. University of Chicago Printing. ISBN978-0-226-00240-eight.

- Baldini, Umberto; Liberto Perugi (1982). The Sculpture of Michelangelo. Rizzoli. ISBN978-0-8478-0447-4.

- Barenboim, Peter (with Shiyan, Sergey). Michelangelo in the Medici Chapel: Genius in Details (in English & Russian), LOOM, Moscow, 2011. ISBN 978-five-9903067-1-4

- Barenboim, Peter (with Heath, Arthur). Michelangelo's Moment: The British Museum Madonna, LOOM, Moscow, 2018.

- Barenboim, Peter (with Heath, Arthur). 500 years of the New Sacristy: Michelangelo in the Medici Chapel, LOOM, Moscow, 2019. ISBN 978-five-906072-42-9

- Carden, Robert West. (1913). Michelangelo: A Record of His Life as Told in His Own Messages and Papers. Lawman and Company Ltd., London; reprinted by Legare Street Printing, 2021.

- Einem, Herbert von (1973). Michelangelo. Trans. Ronald Taylor. London: Methuen.

- Gayford, Martin (2013). Michelangelo: His Epic Life. London: Penguin Books. ISBN978-0-141-93225-five.

- Gilbert, Creighton (1994). Michelangelo: On and Off the Sistine Ceiling. New York: George Braziller.

- Hartt, Frederick (1987). David by the Paw of Michelangelo—the Original Model Discovered, Abbeville, ISBN 0-89659-761-X

- Hibbard, Howard (1974). Michelangelo. New York: Harper & Row.

- Néret, Gilles (2000). Michelangelo . Taschen. ISBN978-3-8228-5976-six.

- Pietrangeli, Carlo, et al. (1994). The Sistine Chapel: A Glorious Restoration. New York: Harry N. Abrams

- Rolland, Romain (2009). Michelangelo. BiblioLife. ISBN978-1-110-00353-2.

- Ryan, Chris (2000). "Poems for Tommaso Cavalieri, Poems for Vittoria Colonna". The Poesy of Michelangelo: An Introduction. London: Bloomsbury Publishing. pp. 94–154. ISBN9780567012012.

- Sala, Charles (1996). Michelangelo: Sculptor, Painter, Builder. Editions Pierre Terrail. ISBN978-ii-87939-069-vii.

- Saslow, James 1000. (1991). The Poetry of Michelangelo: An Annotated Translation. New Haven and London: Yale University Press.

- Seymour, Charles, Jr. (1972). Michelangelo: The Sistine Chapel Ceiling. New York: W.W. Norton.

- Stone, Irving (1987). The Agony and the Ecstasy. Signet. ISBN978-0-451-17135-1.

- Summers, David (1981). Michelangelo and the Language of Art. Princeton Academy Press.

- Symonds, John Addington (1893). The Life of Michelangelo Buonarroti, John C. Nimmo; reprinted by The Modern Library, Random House, 1927.

- Tolnay, Charles de. (1964). The Fine art and Thought of Michelangelo. five vols. New York: Pantheon Books.

- Wallace, William E. (2011). Michelangelo: The Artist, the Human being and his Times. Cambridge University Press. ISBN978-ane-107-67369-4.

- Wallace, William Due east. (2019). Michelangelo, God'due south Builder: The Story of His Final Years and Greatest Masterpiece. Princeton University Press, ISBN 978-0-691-19549-0

- Wilde, Johannes (1978). Michelangelo: Vi Lectures. Oxford: Clarendon Press.

External links

- The Digital Michelangelo Project

- Works by Michelangelo at Project Gutenberg

- Works by or about Michelangelo at Internet Archive

- Works by Michelangelo at LibriVox (public domain audiobooks)

- Michelangelo at the Mathematics Genealogy Project

- The BP Special Exhibition Michelangelo Drawings – closer to the master

- Michelangelo'southward Drawings: Real or Simulated? How to decide if a drawing is by Michelangelo.

- "Michelangelo: The Homo and the Myth"

dillowancterionts.blogspot.com

Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Michelangelo

0 Response to "4 List Some of Michelangeloã¢ââ¢s Famous Works of Art"

Post a Comment